Gaia being in Valdivia, we visited Chile, including the Easter Island, crossed the Pacific Ocean to French Polynesia where a nasty medical problem put a stop to our blue water sailing.

Thierry J.-L. Courvoisier, April 2025

Photographs by Barbara Courvoisier

Having sailed south along the Argentinian coast, around the Southern tip of the Americas and north again through the Patagonian channels (see Flying Fish 2024), we left Gaia for the 2024 austral Winter in Valdivia Chile, at Marina Estancilla. This well protected marina lies 10 M up the Valdivia Rio and another 10 M from the city. Valdivia lies in an earthquake region, like most of Chile, and was deeply shaken in the 1960s when the land sank enough so that large areas now lie below the sea level and are now home of large, lagoons where a large variety of birds live. Following the destruction of the city during that earthquake, the city lost most of its historical heritage. It is now a pleasant town, even if poor in significant buildings.

The marina is as quiet as can be, no shops, neither for the boat nor for the crew, no restaurant, cafe or other distraction. Three or four visiting yachts spend time there. The washing machine and the showers run on cold water. Loud and shaky buses connect the riverside to the city every few minutes during the day. The landscape is peaceful and beautiful. Barges transporting pellets glide down the river every few hours. The marina is safe from the weather point of view and far from any potential human made damage. Gaia spent a quiet Winter there until November 2024, the Austral Spring, when we travelled back from Switzerland with the plan to cross the Pacific to French Polynesia and sail there for some months.

The rio Valdivia as seen from the marina Etancilla

This programme implied that Gaia be checked from the tip of the mast to the bottom of the keel, which we did with the help of competent local technicians. In absence of a facility to lift Gaia out of the water, the hull was looked at by divers. Gaia being a relatively recent boat, from December 2019, and carefully maintained over the years no issue was flagged that could not be solved in a few hours within the two weeks we had allocated for this task.

We had sailed the Chilean Patagonian channels and got to know the fiery winds and extensive rain in the impressive, isolated and rugged landscapes of the southernmost region of Chile. We did want, however, to visit also the central regions and the North of the country while in the region. Friends met in Switzerland and living in the Mole valley in central Chili had invited us to spend a few days with them on their estate. They own a large piece of land on the slope of the valley which they made fruitful by clearing the forest and growing avocados, wines, apricots among other products. Very much in the spirit “Go and make the land bear fruits”. They produce honey, liquor, wine, essential oils, all from their homegrown products. In addition, they built a few cabanas, comfortable and well decorated houses, to host guests and friends. All of this with a magnificent view on the Rio Mole. With them we enjoyed local products and learned about the central fruitful regions of Chile.

Rio Maule, central Chile, the fruitful region of the country

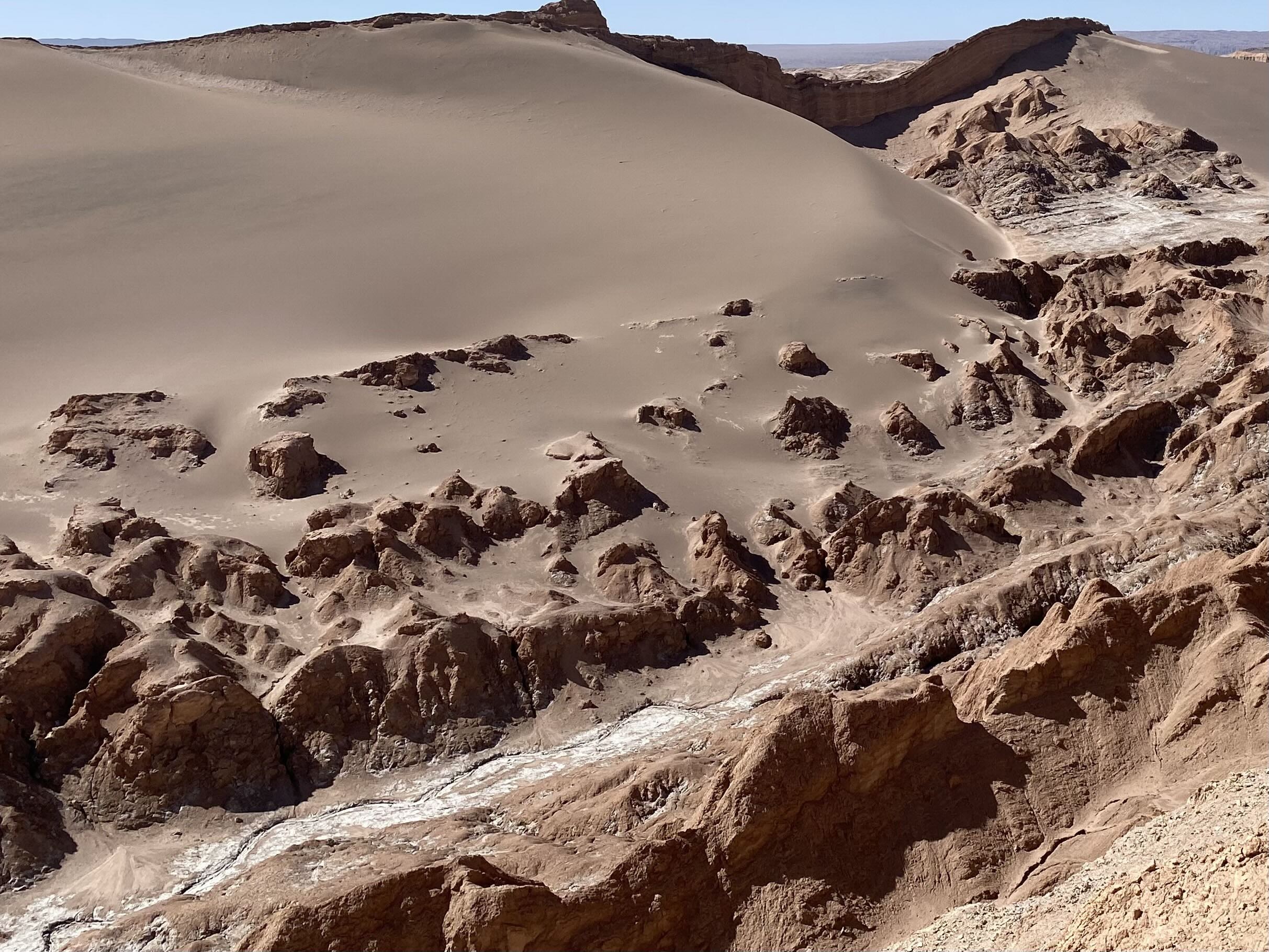

The North of Chile is home of the Atacama Desert, one of the driest regions on Earth. This region is not easily visited by boat as there are no good harbours or marina along the rugged rocky coast of Chili. We therefore flew to visit San Pedro de Atacama, a small touristic city at the heart of a region of breath-taking landscapes. The broad valleys are rich in evaporites, minerals washed down the Andes by the scarce water that evaporates then in the valleys depositing precious minerals (see the Science et voile avec Gaia text on the evaporites: https://sy-gaia.ch/les-richesses-du-desert/). The landscape is so barren at places that one dries out just by looking at it.

Some water in the midst of the desert in northern Chile

Valle de la Luna, Moon valley in northern Chili

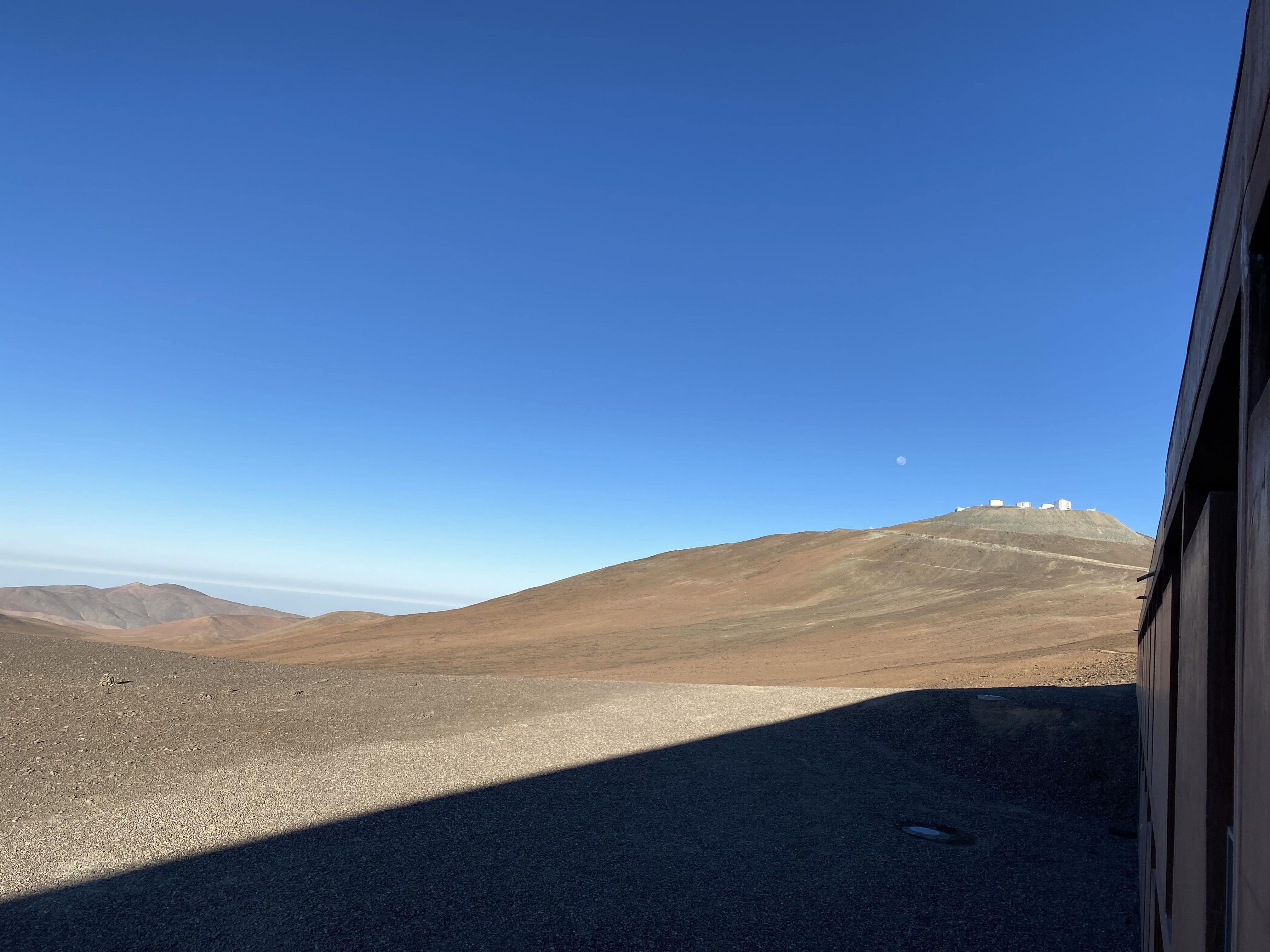

The driest part of the desert is home to the best astronomical site on Earth where one of the best, if not the best, telescope, the VLT, Very Large Telescope, has been built by ESO, the European Southern Observatory. We visited the site and telescope as guests of ESO’s director general Xavier Barcons, a long time friend and colleague. The installation is not a single mirror but four 8m telescopes, meaning that the main mirror of each telescope has a diameter of eight meters. The telescopes can be used independently of one another or combined by interferometry to produce images of a quality that corresponds to what can be obtained by an instrument as big as the distance between the telescopes, i.e. around 100m. This project was conceived in the 1980’s, built in the following decade and is now most successfully operated. See the corresponding Science et voile avec Gaia text, https://sy-gaia.ch/les-grands-telescopes-de-leso-un-raccourci-personnel/, for a personal account of the evolution of large telescopes in Europe.

VLT on top of Cerro Paranal in the Atacama desert

A single VLT enclosure. The mirror inside has a diameter of 8m

The quest to understand the Universe requires now even larger instruments. This is mainly because 4% only of the matter in the Universe is similar to what we are made of or what we can study in laboratories or at CERN. A further 26% of the mass in the Universe is made of a still mysterious matter that feels gravity but none of the other forces of nature and is hence not detected in any laboratory, it is called dark matter. The 70% remaining is even more intriguing as it causes an acceleration of the rate of expansion of the Universe. It as if when you throw a ball up it would accelerate upward rather than slowing down and coming down again. This “matter” is called dark energy. Understanding the history of the Universe and hopefully the nature of its content requires observations of the farthest objects which appear extremely faint from the Earth. A further challenge of modern science is the observation of planets around neighbouring stars, also very faint objects. Observing objects that are this faint requires telescopes considerably larger than the VLT.

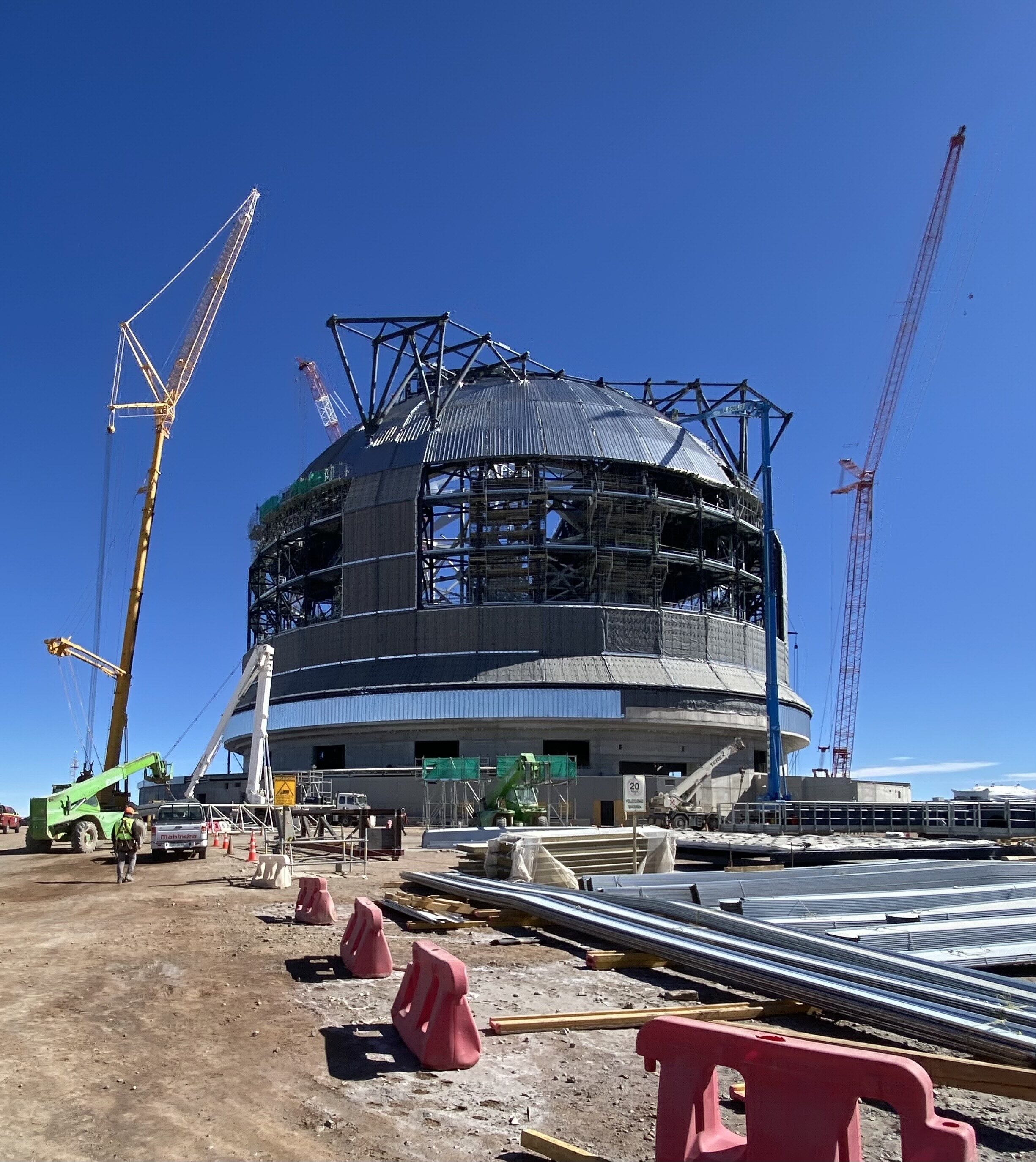

The ELT under construction by ESO. The primary mirror will have a diameter of 39m.

ESO has tackled this challenge by designing and now building a 39m telescope. The main mirror of this instrument is 39 meters in diameter, its area comparable to that of an Olympic pool. This telescope is called ELT for European Large Telescope. The construction site is close to the VLT to benefit from the same excellent sky conditions. We had the privilege of spending half a day visiting the construction of the telescope with the site manager. Combining the sheer size of the telescope and its associated building with the precision needed for high resolution optics is a challenge that ESO is mastering and for the time being is the only institution to do so. The telescope is expected to become operational by the end of the decade.

A stop in Santiago on the way back gave us the opportunity to meet some old friends and colleagues, and a former student of mine now professor in a university there. From Santiago we flew to Easter Island, an island difficult to reach sailing, as our Pacific crossing will prove. While the Easter Island civilisation is fascinating and the landscapes wonderful, the anchorages looked unprotected and rolly, they were devoid of any sailboat while we were there.

An archeological site from the Birdman civilisation on Easter Island

The large Easter Island sculptures, mohai, were cut in the rock of this stonepit

Back on board in the last days of the year, it was time to start provisioning for the Pacific crossing and for some time in French Polynesia where shops are said to be few and far apart and, we were told, very expensive. Valdivia was the right place to buy wine, beer, flour, pasta, rice and canned food. Fresh products would come later, in Algarrobo.

January first our crew, Uwe Koehler, arrived from Switzerland. He is an experienced sailor, serves as a skipper on boats of the Cruising Club of Switzerland, CCS, and was keen to sail the South Pacific. January 4, having informed the capitania in Valdivia, we left the marina Estancilla for a 10M sail down the river Valdivia to its mouth in Puerto Corral. This was the opportunity to test all sails in a fresh breeze and to see with satisfaction that we had set all ropes and sails properly. We spent the night at anchor on soft mud of moderate holding, but acceptable in the prevailing conditions. We left the next morning for Algarrobo, some 400M North, which was to be our last stop on the American continent.

Gaia’s crew to cross the Pacific: Uwe, Barbara, Thierry

A night in Puerto Corral at the mouth of rio Valdivia

There are very few, if any, safe anchorages along this rugged coast. Algarrobo is one of them at least in the southerly winds that prevail in Summer. The sail was bumpy and windy, good conditions to test the crew and to establish a shift system. Algarrobo is a small marina run by the Cofraderia del Pacifico, an organisation that strived in the military dictatorship time for, we were told, rather well to do people close to the system. The entrance is barely wider than Gaia and prone to swell. Informed of these conditions, we had called and were met by staff who showed us the way inside the marina to a berth at the very end of the marina next to a bird sanctuary. Seagulls, pelicans, hawks, circled in the evening sky providing a wonderful and noisy ballet. The downside of this proximity was that we had to clean the deck every morning. Good friends of ours live close to Algarrobo, their presence in the region was the main motivation for our stop there. We visited them for a couple days, provisioned fresh products and did the paper work required to leave Chile.

Algarrobo. Gaia in the marina and the bird sanctuary

Birds are kings in Algarrobo

We enquired upon arrival, when announcing our arrival in the capitania as required in Chile, about the procedure to leave the country. We were told that we should go the following days to the immigration office in San Antonio, a large commercial port and city some 35km from Algarrobo. Although an important harbour, San Antonio has no possibility to accept sailing boats. We therefore had to drive there, which we did with our local friends. The conversation at the immigration office was easy with the help of our Spanish speaking friends and pleasant but fruitless: we were told to come back shortly before leaving. During a second enquiry at the capitania in Algarrobo few days later, we were told to drive to the customs’ office, also in San Antonio to obtain a form that was to be filled, brought back to the capitania and then again to the customs’ office in San Antonio. The marina provided a driver for these trips up and down the coast. The custom officers in San Antonio told us that the papers we had were fine, no need for a further form, but that they could not deliver the permission to leave the country there, one of them would come to Algarrobo to see us leave. Back to the capitania in Algarrobo, we filled some more papers, always with the same information about boat and crew, and were sent for a further fruitless trip to the immigration office in San Antonio where we were told that, like the custom officers, one officer would come to Algarrobo and stamp our passports at the time of leaving. At our next visit to the capitania in Algarrobo we were told after a long wait, that the port captain would come in person to the marina to wave us off. Coordination between offices seems to require driving lots of kilometers up and down the coast. Maybe that in some distant future telephone, fax or even e-mail will be put to use rather than burning gasoline for trips up and down the coast between offices.

The next morning, the day of our announced departure, we went to the fuel mole, filled our tanks and waited -three hours- for all these officials to arrive, hand us papers and stamp our passports. The last one was the port captain who filled, by hand, a page in a very official looking booklet with again the same information on Gaia and her captain. He asked me to sign the page and authorised our departure. Don’t worry if you forget the details of this procedure, I doubt that it is twice the same. The South American bureaucracy has an endless imagination.

The marina entrance had not grown any wider since our arrival and the swell had increased as had the wind, making the exit as exciting as the entrance, but we were at last on our way.

We had hoped to be able to make a stop in Juan Fernandez, the island of Robinson Crusoe. This proved not possible. We were told by the authorities in Algarrobo and San Antonio that there is no administrative possibility to leave Chile from there. This had not prevented Songster, an OCC yacht skippered by Jurrian whom we had met in the Atlantic and in Patagonia, to stop there, but prevented them to leave officially Chile. They will see the next time they visit the country whether this bears any consequence. For us a nasty depression on the island when we could have visited solved any hesitation.

Leaving Algarrobo (33o S), our route was North West to 22o S. We then sailed West to come down South again on the Gambiers (23o S), the first Polynesian archipelago on our path. We started in a fresh southerly wind which made for a fast first few days, followed, as expected by easterly winds. The sea was never really comfortable and remained bumpy for most of the way. The days followed one after the other, the landscape remaining unchanged, making me wonder why we should work hard to be tomorrow at a place that looked identical to where we were today. Even the chart had nothing to show. We saw one cargo ship on the second day of our crossing. The officer on shift bluntly refused to alter his course to prevent a collision, a rare occurrence. Few days later we saw what was probably a Chinese fishing vessel devoid of AIS identification. And we were called on the 20th day by a container ship that we did not see. The officer on shift asked whether everything was well on board. We saw very little marine life, a few dolphins a couple of times, and some birds. Every few days we changed the board clock by one hour arranging the board time so that the sun set between 7pm and 8pm, after dinner.

Underway somewhere on the Pacific

Easter island proved also difficult to reach. We were quite some distance North of it when a depression was born close to the island. This depression prevented our visit and was the cause of westerlies on our route. The tactics to minimise the discomfort of sailing against the wind was devised with Pierre Eckert, our meteorological expert. We sailed South West for 24 hours before turning West again. Unfortunately, the centre of the depression was poorly defined, a situation often met in these waters where ground weather stations are few and far apart. We found ourselves close to the centre of the low pressure system with no wind, endless massive grey clouds, sometimes pouring rain and a very confused sea. No fun. We motored for some 12 hours to get out of there. This was followed by two days of wonderful south-westerlies under a brilliant sunshine and wonderful night skies. The Milky Way was clear, the Large Magellanic Cloud, a small galaxy close to the Milky Way, and even the Small Magellanic Cloud, another even smaller galaxy in our vicinity, could be clearly seen. In the Milky Way, a region close to the centre appears much darker than its surroundings. This dark cloud, the Coal Sack, is not due to any lack of stars, but to the presence of an extended region of dust that absorbs the light of the stars. This pleasant period did not last long, before another weather system disturbed the trade winds and replaced them by again poorly modelled westerlies in high uncomfortable seas. The last days of the crossing were more of a punishment than a bliss, as we tacked repeatedly to make the best of the wind shifts.

Close to the center of a depression north of Easter Island

We were 30 days at sea for a 3900M crossing. The provisioning, overseen by Barbara, had been excellent. She put under vacuum a number of fresh items, meat and vegetables, with the result that we had fresh vegetables to the end of our crossing. Thanks to Barbara, Gaia was certainly the best table on the Pacific while we were there.

Vacuum packed vegetables were good for 30 days

The main pass into the Gambier atoll is in the North West, it is the only one that is marked. However, Jurriaan, Songster’s skipper, had used the South East pass some time earlier and assured me that it could be used without danger. Since it was the only one on the lee side of the archipelago when we arrived, we did use it. But it was only when within the lagoon that the conditions grew milder. The last difficulty was the large number of pearl farm buoys between the islands, also along the routes within the archipelago. This mastered, we arrived at the anchorage in front of Rikitea, a small settlement, albeit the main one, on the island Mangareva, the largest of the Gambier. We anchored and were greeted by the Crews of Songster, of BoatyMcboatface and of Ithaca, who had also sailed the Patagonoian channels a year earlier. More friendly boats were around us, among them Yalow and Melania, of which more later. Fruits and vegetables were offered together with a warm welcome.

Land in sight, the Gambier archipelago

The day following our arrival Rolf and Wolf, the crew of BoatyMcboatface, showed us around: the garbage collection spot, the minimarket, the medical outpost, the gendarmerie, where we were to announce our arrival, and the much too large church for such a small community; a reminder of the role of missionaries in the region during the second half of the XIXth century. All this along the 700m main and only street. Rikitea is provisioned twice per month by a small cargo ship which also brings fuel to the island and the yachties. This was to be three days after our arrival, on Monday. The fuel is sold and delivered in 200l barrels, the content of which has to be poured or pumped into jerrycans which are carried to the dinghies, brought on board and poured into the tank. An operation for which we borrowed a number of jerrycans from surrounding boats at anchor. The operation was long and physically strenuous, but it all went well. A windy afternoon followed on Wednesday when we had to re-anchor before we could start thinking of enjoying the Gambier so often described as a paradise for sailors.

Rikitea on Mangareva, Gambier

Enjoying the Gambier was, however, not to be. My urinary track got blocked in the night to Friday. A deadly problem if at sea without the proper tools and knowledge, a major hassle still in Rikitea. The nurse and medical doctor at the medical outpost (they live on a boat in the anchorage) were knowledgeable and equipped to insert a catheter on the Friday morning and thus saved my life. This did not solve the problem though. I had to fly to Papeete the following Tuesday, a four hours flight twice a week, meet a urologist some days later, hear that a surgical intervention was necessary, undergo all medical checks required for the intervention, and be operated. All this happened during ten days while Barbara stayed on board at anchor in the Gambier in a very stressed state. Uwe, our crew, developed a weakness and fever during that time, leaving Barbara with very little support on board. For Barbara to join me in Papeete by flight as soon as possible after the intervention, it was necessary to have Gaia convoyed to Papeete. This was done by the two lady skippers of the neighbouring yachts Yalow and Melania. One of them, Mélanie, is a professional of the sea, she and Daniela of Yalow are seasoned sailors knowledgeble of the region. They offered to sail Gaia the 800 M to Papeete and did this with Mélanie’s daughter, leaving their boats unattended in Rikitea. This generous offer by competent sailors was an immense relief for us. Other crews, like those of Songster and BoatyMcBoatface kept a caring eye on Gaia and her crew while I visited the necessary medical offices in Papeete. They delayed their departure from Rikitea until Barbara left for Papeete. The help we received from all our friends anchored around Gaia cannot be overstated.

While I was in Papeete in a somewhat diminished state and Barbara on board Gaia at anchor in Rikitea, communication between us was important. The Gambier including Rikitea is in a rather underdeveloped state with regard to connection with only a 2G network that does not allow data, hence no whatsap or email. For people like us resisting starlink and its thousands satellites modifying the night sky for the whole of humanity and causing major problems to scientists working to understand the Universe, this is a problem. Friendly crews like those of Yalow and Songster were kind enough to anchor close to Gaia so that their starlink signal could be captured on board. This shows once more the help we received and illustrates the ambivalence of our posture with respect to starlink.

This note is written while Barbara and I recover in Papeete. Looking back at the last weeks, we realised that a urinary track obstruction at high sea can be deadly. Indeed, Tycho Brahe, the astronomer on whose data Kepler built his famous three laws, died of a similar problem in very intense pain in 1601. We did not carry a urinary catheter on board Gaia, a circumstance that would probably have led to my death, should the problem have arisen during the Pacific crossing. It is hard to imagine the trauma for Barbara should this have happened. The decision to not have a catheter on board was clearly wrong. The right decision would, however, not have been to just carry one on board, but should have included learning how to put one in place in an acute situation. Indeed, driving the catheter through the obstruction requires applying quite some strength and inflicts a pain the like of which I had never known. Circumstances that make a rather straightforward procedure much more difficult.

The tension we lived through during the last weeks, our advancing age and obviously not so strong health mean that we bring our blue water sailing to an end. This involves parting with Gaia which is now for sale here in Papeete.