CERES through Russian inner waterways (part two)

Thierry J.-L. Courvoisier

We sailed in July 2016 from Helsinki towards Saint-Petersburg and further east through the Russian inner waterways to the White Sea and the Barents Sea with the idea to arrive in Tromsø in early September. The first part of this trip, up to Voznesenye on the shore of lake Onega, may be found in Flying Fish 2018-1.

Fig. 1 Cérès in Voznesenye

The following day, July 31 2016, was a beautiful day to sail north, along the west shore of the Onega lake, with winds from the south-west force 4 to 6 on flat waters under a bright sunshine. We set off early for a long sail towards Petrozavodsk, which was, however, too far for a single sailing day. We therefore spotted a well protected although rather large cove on the west side of the lake, where we could stop for a night. The shore along which we sailed was devoid of human settlements and covered by a thick forest. The bay in which we dropped anchor was large, calm, rather shallow, so that we had to stay in its middle, almost circular. Forest was everywhere, except for a few houses on the northern strand. One other ship was at anchor in the bay, soon joined by a flotilla of smaller boats, equipped with fishing gear, that appeared from nowhere when the sun slowly went down. As elsewhere on these waters none of them came anywhere near us or made any sign of even seeing us. The sun set in glorious colours, the wind had completely died, the forest was quiet, not a sound was heard.

Fig. 2 A bay along the west shore of lake Onega

We reached Petrozavodsk the following day. Although this is a larger city from which a number of boats and hydrofoils carry tourists to Kizhi, an important site we were to visit few days later, there is no harbour. We had been told by Vladimir, the OCC port officer in Saint-Petersburg who helped us prepare our passage in the Russian inner waterways, to tie at a naval museum run by Victor Leonidovich Dmitriev. We had also been warned that, while the approach to the museum pier is in relatively deep water, there are underwater stones and obstructions, neither of which are visible or marked in any way. I was therefore rather nervous while approaching until our phone call to Victor had been answered and a man, who turned out to be Victor, appeared at the extremity of the quay and started to make wide signs indicating the course to follow to near the pier while avoiding the obstructions, somewhat like airport staff guiding docking planes. This was successful in the calm conditions of that day and we arrived without incident. The wooden pier, some 20m long perpendicular to the shore, was poorly protected from the lake by few rusting wrecks. A rather odd ship was moored on the other side of the pier. It reminded us of a galleon of times past: very high on the water, short and broad, with two masts and a long bowsprit. In some ways the presence of such a ship was not a complete surprise in a museum. More surprising was the fact that she looked all fit and ready to go. And indeed a man came on deck telling us that they were preparing to leave the next day for Kizhi, where a sailing school was about to begin. That man was very helpful, he drove me to the nearest fuel station with a number of jerrycans so that we could fill our reservoir. We also took our empty camping gas bottles to have them filled at a nearby gas plant, where the smell of gas was pervasive and somewhat worrisome. The staff was at first unsure about our request, but were eventually convinced and successfully refilled the bottles. Getting water, which we also needed, was more difficult and indeed impossible anywhere near the pier and museum. Tap water was, we were told, not potable, even boiled.

Fig. 3 The pier at the maritime museum in Petrozavodsk

Fig. 4 Wrecks protecting the museum pier

While talking, our new friend told us that he had been the first man to circumnavigate the Scandinavian peninsula. When the Belomorsk canal, that we would also sail along few days hence, was opened to civilian navigation in the early 1990s as a consequence of the Perestroika, he had set sails on a boat constructed by a group of enthusiasts from the region. They sailed north, reached the White Sea through the canal, sailed the Barents Sea to the North Cape, than south-west along the Norwegian coast, into the Baltic Sea to Saint-Petersburg, up the Neva river to lake Ladoga and along the Svir river back home.

Petrozavodsk is a medium size city of some 260’000 inhabitants, it is the capital of the Karelian Russian republic and a hub for tourists traveling to Kizhi. There is an interesting museum in the centre of the city, where one learns about the geography and history of Karelia, the large region that spans the north-west of the Russian Federation and the eastern part of Finland. One reads there that the city was founded and prospered in the XVIIIth century following a decision by Peter the Great to establish an arm and ammunition factory. Hence the name of the city: the factory of Peter in Russian. Its location had been chosen some distance from Saint-Petersburg to be safe from attacks from the Baltic sea, upstream so that transport to Saint-Petersburg would be easy, and within easy reach of iron ore and coal, the main ingredients to manufacture weaponry. The history told by the museum ends at the end of the XIXth century, the events of the last 100 years being conspicuously absent, replaced by rather uninteresting folklore considerations. It is as if the recent history in that region is still too fresh and the wounds too raw for the population to come to terms with it.

Fig. 5 Lenine is still in good shape in Petrozavodsk

The city museum is opposite a nice building hosting some ministry in front of which a lorry carrying a water cistern was stationed. Women who were obviously secretaries and administrative staff in the ministry emerged from their offices in high heels and tight robes to fill tea kettles at the cistern. Tap water was evidently not appropriate even to boil tea. This explained why we could not find any water to fill our tanks anywhere close to our pier. Drinking water was, however, to be bought in supermarkets, which hold large supplies of five or eight litre bottles. We therefore filled the boot of a taxi with a number of them and would do so wherever possible during the following weeks to fill our tanks and keep dinking water on board.

Fig. 6 Getting drinking water in front of the ministry

Two big and aggressive dogs were staying on the premises of the museum where we were moored. Victor warned us that they would be harmless while he was around, but that they would attack and could kill anybody at night when he had left. We were therefore told to not leave our boat under any circumstance from evening to morning.

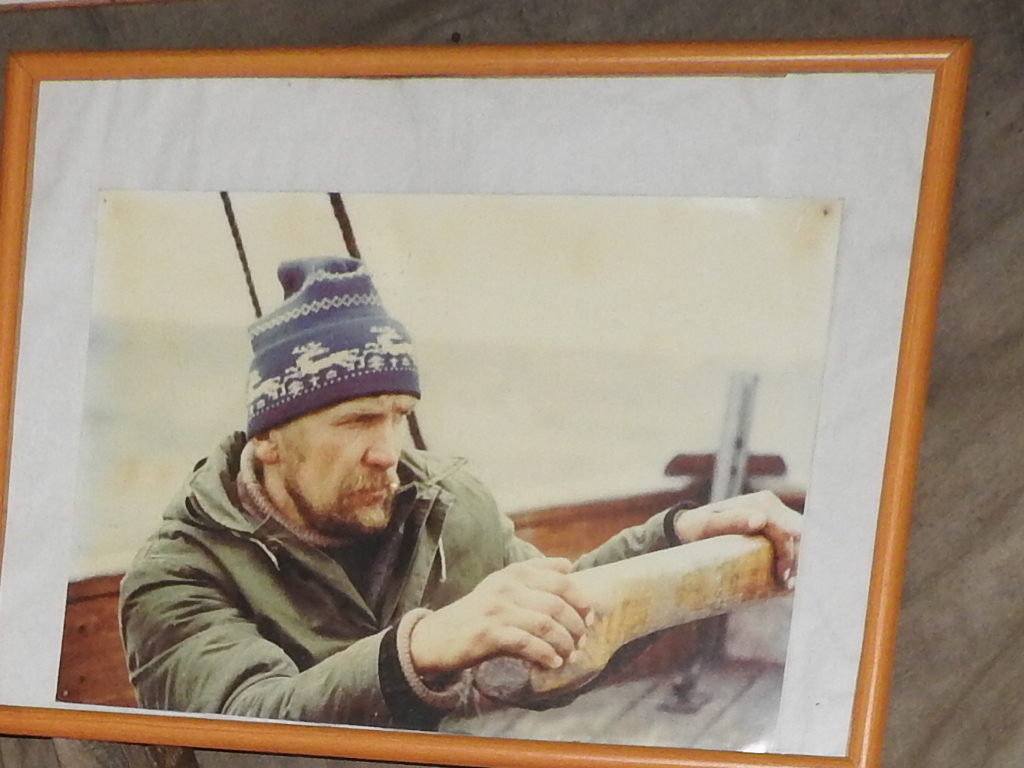

When Victor proposed to lead us through the museum and premises, we expected a rather dusty collection of possibly rather uninteresting local tools and objects. And indeed Victor guided us to a large wooden platform half floating and half ashore, where it had been washed up by a storm. This position reinforced my feeling that, were the weather to turn bad, Cérès would be neither protected nor safe. The interior of the wooden shed that stood on the half stranded barge was indeed dusty and showed old photographs on the walls. The story these objects told was, however, most astonishing. The first photograph we were shown depicted Victor, some years younger, forcefully handling the massive tiller of a wooden ship. The picture had been taken, so he told us, on another self-made boat they had sailed to Svalbard. The ship had an open deck, no engine, but oars. An old hand-powered radio was all the communication equipment on board. So intense was the thirst of discovery of the group of people on this lake shore that they sailed as soon as it became possible in the 1990s by all means out in the world, and to the most hostile waters.

Fig. 7 Victor at the tiller on the way to Svalbard.

On their way back from Svalbard the group led by Victor grew somewhat mystic and decided to pursue their efforts towards openness, love between peoples and therefore to sail to Israel in order to visit Jerusalem. For this adventure they built three boats, this time in the Viking style, equipped with one mast and one square sail. Once ready they organised a baptism ceremony for their ships to which church dignitaries and Boris Eltsine took part. They then sailed off, south this time, to the Volga, Moscow, the black Sea, Turkey, and east to the end of the Mediterranean Sea. After making their pilgrimage to Jerusalem, they turned west, and sailed all the way to the Atlantic. There the project seems to have run in difficulties. Ukraine had become independent of Russia. The Ukrainian members of the team claimed their independence from the rest of the project, they sold their boat leaving the others to struggle back to Russia, which they did without visas and oblivious of any custom or administration rule. Finally we were shown the next boat under construction. This one looked somewhat like an XVIIIth century ship. The hull was there in rough planks, the inside structures barely started. It was beginning of August and their plan was to set sails on this boat in October of that same year to travel around the globe, carried by the same ideal of world love and peace. In comparison with the adventures of our hosts in Petrozavodsk, our navigation on a solid modern yacht equipped with charts, electronics and winches gave the impression of being an amiable Sunday trip on a quiet pond. Our exchanges were concluded by the signatures of mutual books, exchanges of Swiss wine, Vodka, some flags and pictures.

The following morning Viktor appeared as we set off and waved us again through the unseen stones and obstacles to the open waters of the lake. We crossed the northern part of the lake eastward before entering a maze of long islands all oriented north-south between which a well marked channel helped us find our way to Kizhi.

The main building in Kizhi is a large wooden church dominating the shore of a straight between islands in the northern part of the Onega lake. There is a quay for the numerous visiting tourism boats and hydrofoils and a small pier for private boats where we were expected to dock. Since there was not enough water for our draught we dropped our anchor beneath the church in a calm and warm weather that enticed all crew to take a dip and spare the water of the showers. Swimming next to Cérès beneath this massive wooden church on a hot afternoon in the high latitudes of western Russia was an unexpected most pleasant experience.

Fig. 8 Cérès at anchor in front of the church in Kizhi

Kizhi is a massive church, it is also an area where a number of Karelian buildings have been transported, re-built and put to display for visitors. A visit had been organised for us, it was conducted by a young lady, Anna, with whom it was a pleasure to interact for some hours on that day and the following one, while touring the island on rented bikes. The nautical school opening took place while we were there. The style reminded me of scouting decades ago, although some nervousness could be perceived, caused by a fatal accident in a similar camp some weeks earlier in another region of Russia.

Fig. 9 The church in Kizhi in the evening light

While some of us would have liked to stay somewhat longer, the charm of our guide being not completely estranged to this wish, the long route in front of us, that included rounding the northernmost coasts of our continent rather late in the season, encouraged us to leave sooner rather than later to reach the southern end of the Belomorsk canal in Povenets. This was a 12h sail at first in the islands north of Kizhi, than in the long and wide northern tip of the Onega lake. The day began under a pleasant quiet weather and ended with a fresh, humid and cool south-west breeze.

Povenets is a poorly sheltered harbour open to the south where we expected a long stone quay. Our contact there should have been Konstantin, the maritime security officer for the lake and the Belomork canal, another person warned of our arrival by Vladimir. But Konstantin was not available at the time of our arrival and had provided the name of another person to call and prepare our arrival. That person was not in charge anymore and redirected us to Dimitri and Misha who finally expected us, but seemed to have little or no understanding of nautical practices. The quay was busy with a cargo ship being unloaded of gravel by a floating crane leaving some room for us in the swell along the high stone quay. Uncomfortable to say the least. We were, therefore, redirected alongside an old patrol ship in a somewhat quieter spot of the harbour but 1.5m only from a rusting half sunken wreck. We tied there after having carefully hand sounded to check whether the grey-brown water did not hide some pernicious obstacle and after an old man who seemed to have some responsibility for the patrol ship removed his fishing gear.

Fig. 10 Cérès alongside an old patrol boat in Poveniets

Once confident that Cérès was reasonably safe for the length of our stay we were given a form by Dimitri who requested some payment for staying there, assured us that that Konstantin would come on the next day to tell us all about the Belomorsk canal and whom we asked whether it would be possible to get a taxi the following day to visit the surroundings. Walking around the harbour led us to some housing buildings few hundred meters away, not much more in the grey humidity of the morning. Misha appeared again in the late morning telling us that no taxi driver had agreed to drive us around, but that he would do that himself, for which we were grateful as we did want to visit Sandarmoh, the area where thousands prisoners had been shot in the late 1930s. Prisoners from the several camps in the north of Russia were then regularly gathered, shipped, for example from the Solovki islands to the continent, assembled by groups in the evening, robed of all their clothing, transported by lorry to Sandarmoh and shot in front of open graves. They were mostly young men, some convinced almost to the end of the virtues of the Bolshevik system, thinking that they were victims of judicial errors in an otherwise benevolent system. One such story may be read in “Stalin’s Meteorologist” by Oliver Rolin.

Sandarmoh is now a forest in which many trees hold a photograph of a victim. The Soviet archives had been open for some time in the middle of the 1990s, which allowed historians to locate Sandarmoh and to find the names of at least 6000 victims registered now in a blue binder in a small chapel on the site. The earth is uneven in the forest testifying of the incredibly large number of anonymous collective graves in the area. The forest is young, possibly dating from the period of the perestroika, when the significance of the area was recognised. The photographs show young and bright faces illustrating characters that were prevented from contributing to the emerging society that many of them had welcome. Few monuments have been erected by communities, the Jews or the Poles for example, to commemorate “their victims”. Modern Russians resent these because they suggest that Stalin’s purges had been specifically aimed at identifiable communities, whereas we were told on several occasions that the police and political actions had made no difference of origin or religion of the victims. Erecting these monuments now seems to be used as a political message fostering tensions between modern Russia and the communities for which the monuments stand rather than remembering the suffering of a whole people.

Very few people were seen on the site, which is barely indicated from the road. Archives had been opened, the memory awakened, some 20 years ago, but the book was closed again. And the site left to its quiet sadness.

Fig. 11 Forest in Sandarmoh where thousands of prisoners were shot in 1937-1938.

In the mean time Konstantin was said to arrive in the evening and our guide organised a barbecue that was to take place on the quay in the wind and rain. Misha explained that with Dimitri and another associate they rent the harbour facilities from the State for the equivalent of some 30 Euros per month and may organise whatever activities they deem appropriate, and financially rewarding. Hence the gravel unloading and their careful counting of the lorries that came and went. He told us of bold plans to build a better protection for the harbour and to dredge it to suitable depths to be able to host yachts. Plans that seem widely overstretched for the handful of boats that pass by every year, although the tax they required from us amounted to not far from their monthly rent of the quay and facilities, of which there was none.

Konstantin finally arrived late at night after several hours of standing in the cold, drinking beer and eating grilled chicken. We saw a massive powerful man emerge between the headlamps of a large car to bring more food and vodka. The fire was reanimated and the evening went on for some more hours. Rendez-vous was finally taken for the next morning so that we could obtain the instructions we needed to sail the canal.

This done in the morning Konstantin insisted to take us to visit nearby Mdweschjegorsk, its train station and forts overlooking the lake built by Finnish prisoners in the 1940s. Following this we could not leave before trying Konstantin’s “bagna”, the Russian equivalent to a sauna in his home. This involved not only fire and steam, but also large quantities of vodka. A long afternoon and evening to learn, among many other subjects, that the worries of the Russian people deal much more with local considerations like water quality and sewage than with the importance of Russia on the world checkerboard; that the type of activities undertaken in the harbour do not lead to any significant development for the region and that the lake is safer when the old patrol boat alongside which we were moored stays at quay. There was enough time also to meet the officer responsible for other aspects of the security of the region before hiring a taxi back to Cérès in the middle of the night.

We were than free to leave Povenets the following morning for the first lock just a couple nautical miles away.