This is a description of a sailing cruise my wife, Barbara, and I did in the Summer of 2015. It will be published in the journal of the Ocean Cruising Club, Flying Fish in 2016.

Barbara and I sailed on board Cérès, our Centurion 40S, from Tallinn in Estonia to Finland from mid-July to mid-August 2015. This is the latest leg of our navigation in the Baltic Sea. We enjoy sailing up in the North, where the light does not end during the Summer weeks.

Cérès under sail in the Finish archipelago

Leaving Tallinn in Estonia on the south shore of the Gulf of Finland for Helsinki in Finland means leaving the Hanseatic world. The Hanseatic league was a union of North European cities organised to foster maritime trade, that flourished during the Middle Ages until the XVI century. Cities like Gdansk, Riga or Tallinn, but also Bergen and Koenigsberg (now Kaliningrad) belonged to this league, a centre of which was the island of Gotland in the middle of the Baltic Sea. The architecture and quality of the building materials in these cities is a testimony of the wealth brought by this organisation. Some of the “local” specialties still to be found in modern shops give a clear indication of the extent of the exchanges. Thus Tallinn is proud of its marzipan; and some go as far as claiming that it is there that it was invented in the Middle Ages. Since almonds, the basis of marzipan, do not grow in the cold marshes of Europe, but rather in the warm climates of the South and Eastern parts of the continent, the tradition of producing marzipan testifies of long lasting links between the Baltic Sea and regions of the Middle East. Tallinn and the other Hanseatic cities were thus the maritime end of long terrestrial routes that linked Northern Europe to the rest of the then known world including China and the Middle East.

The roofs of the Hanseatic city Tallinn

None of this is true of Helsinki. The long tradition of trade with southern regions ends on the south shore of the Baltic, its northern shore testifies of the harsh life styles of the Vikings rather than the sweets of international trade. There is no sophisticated Middle Age stone building in Helsinki, but rather many early XX century constructions, that tell a story of prosperity developing at that time. Older buildings are often in wood, brightly coloured and harmoniously shaped.

A section of the long shore line of Helsinki

Leaving the south shore of the Baltic sea is also leaving long straight shallow coastlines of sand beaches, dunes and forest, that extend for many miles with very few good natural harbours. The latter are naturally where the Hanseatic cities prospered. On the Northern shore of the Gulf of Finland one finds no sandy beaches, but rather, the granites of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The distance from Tallinn to Helsinki is some 45 nautical miles across the golf of Finland. The route is easy. If in doubt of the right direction, one can simply follow the ferries crossing many times per day between the two cities. There is almost always at least one in sight in either direction. Arriving from the south, the coast is preceded by a reasonable number of islands with clearly marked channels leading to the many harbours of the city. No problem there either, provided that ships are avoided.

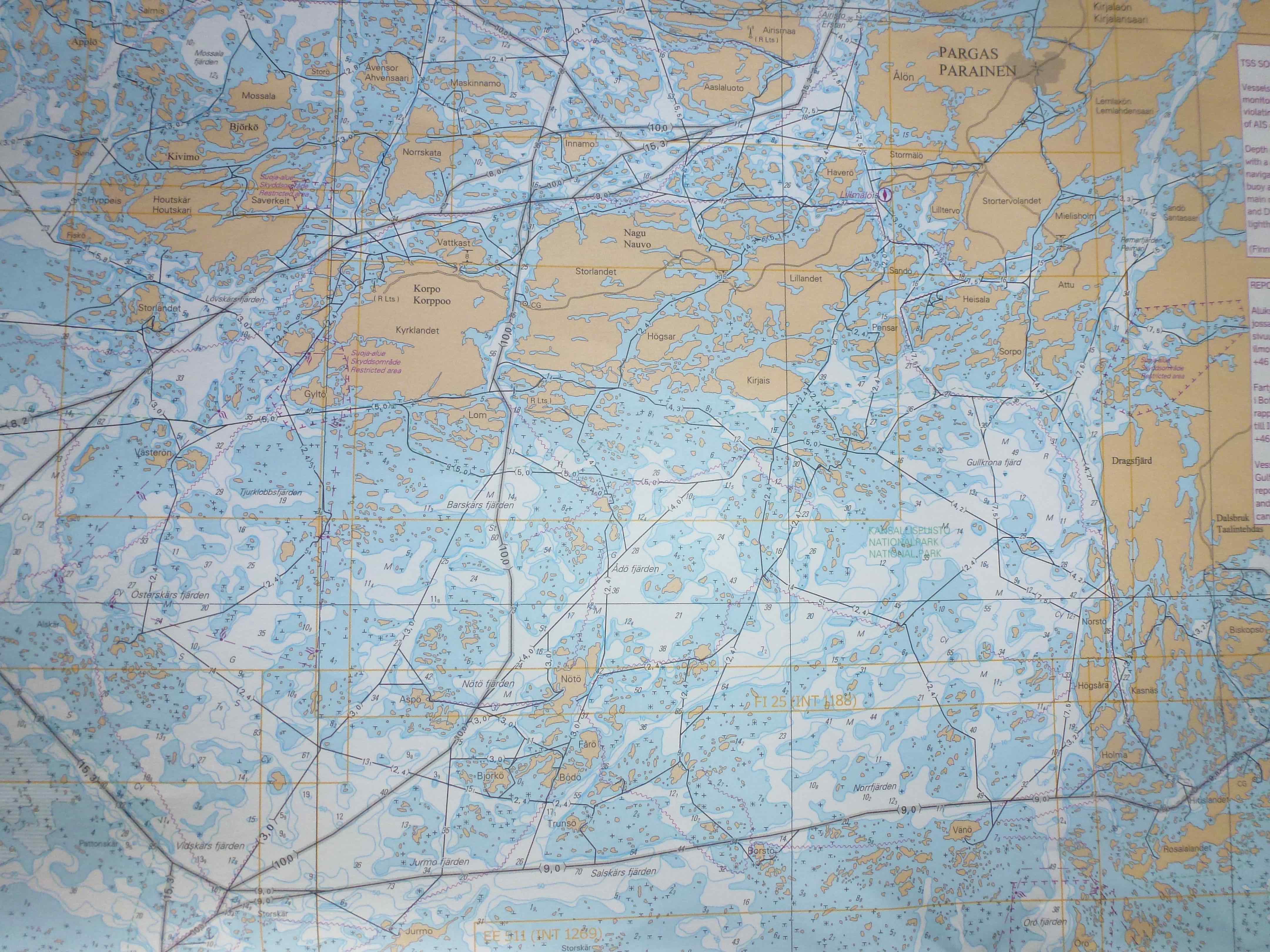

We stopped at the Helsinki Sailing Club, HSK, on Lauttasaarri island, a very friendly harbour for visiting yachts in the immediate vicinity of which all facilities, ship chandlers and chart shops can be found. Kalevi Westersund, a former president of the club, whom OCC port officer in Saint-Petersburg Vladimir Ivankiv had indicated as a helpful and reliable contact in Helsinki, welcomed us warmly, indicated the way to the sauna, and helped us getting started in the preparation of our Finish navigation. Indeed some preparation is necessary before sailing away along the coast, as the “reasonable” number of islands off the coast of Helsinki does not prepare the newcomer for the challenge of sailing in the completely unreasonably dense mesh of water and land that one finds elsewhere in these “waters”. Our first call was therefore to the chart-shop in order to find those charts and documentation that we would need to cruise in the Finnish waters. Looking at the charts, it is immediately clear that sailing between Helsinki and Mariehamn in the Golf of Bothnia is not like sailing in open seas from A to B. Moving along the Finnish coast, one quickly sees that the reasonable number of islands just South of Helsinki is soon replaced by a maze of rocks, islets and islands. The sea is littered with rocks and islands of all sizes, from a meter or less to kilometres. The highest ones dominate the sea by few tens of metres, the more treacherous ones are covered by few centimetres of water. Routes are marked on the charts to guide boats and ships. The maximum draught allowed on any route is indicated. Navigators met in HSK warmly recommended that routes be followed, as the regions surrounding them are not reliably described on the charts. And indeed we were told that a boat had hit a stone indicated at a depth of 6.1m while approaching a known anchorage. After enquiry, the skipper learned that a mistake had been made and that the depth indicated on the chart should read 1.6m rather than 6.1m. The subsequent editions of that chart were corrected. The maze of stones made it easy for me to be convinced that we would follow the routes.

Chart of a part of the Archipelago. Routes with maximum allowed depths are indicated. We did follow them with attention and precision.

Following the routes is then straightforward, provided that continuous attention is given to the navigation in the restricted meaning of the word. There are a huge number of marks, most in the cardinal system, but some red and green. All must be followed without missing any as the route winds between large and small rocks. At times the passage is barely wider than a couple boats lengths, allowing a detailed look at the texture of the granite. Precision is requested at the helm that cannot be trusted to the autopilot for any length of time. In addition to the marks in the water and the little lighthouses, one also follows leading marks and lights. Large red and yellow panels, which indicate a segment of route with precision when superposed. Some are large enough to be seen several nautical miles away.

Leading marks in the grey Finish Summer 2015

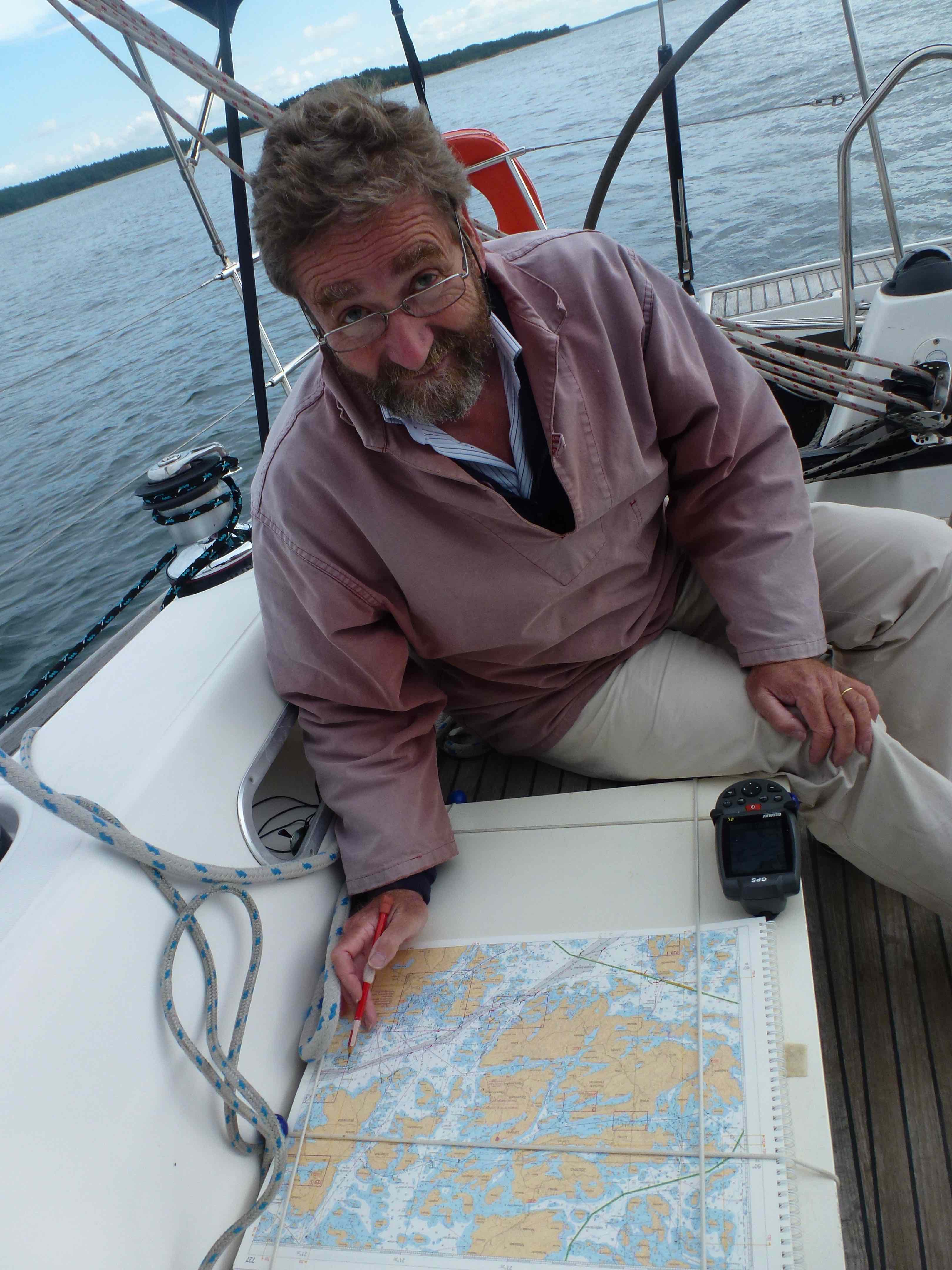

My solution to avoid getting lost was to take the paper chart in the cockpit, install a portable chart plotter next to it and tick all significant marks on the paper chart, as they were identified on the charts and in the real world. Looking at the way the local navigators behaved indicated that they followed similar routines.

Barbara at the helm as we follow a tricky route in company

Following a route, the chart part.

At the end of a day’s sail, we had seen hundreds of such marks, we had rehearsed ad nauseam that you pass east of an east mark that you hence leave it to your west, and west of a west mark that you therefore leave to your east and so forth. At the end of the day it was necessary to drink a solid beer followed by some considerably stronger beverages to straighten our cerebral cells again and get them ready to find north and south properly on the following day.

Straightening neuronal cells after a long navigation and preparing the next one.

Our navigation took us west from Helsinki in the direction of Hanko and Kasnaes, where we met with OCC port officer Tom Tigerstedt. Tom told us how we could identify spots to stop for the night, and how to relate the chart information to the documentation in our possession. From then on we had all the tools and tips needed to navigate safely and find suitable harbours and anchorages.

In the course of the month we stopped at a number of places, some rather small, where the first thing we were told upon arrival was how to find the sauna. We soon understood that saunas are an essential element of the Finnish way of life. In HSK it is even so that during the winter, when all boats are out of the water for fear of ice, the sauna opens every week for members to gather and share a beer, naked in steaming heat. Apartment buildings have their saunas in which the inhabitants also regularly meet. Sailing along the islands and coast it was not unusual to spot naked silhouettes on the shore on their way between sauna and sea or back. It is therefore so that that in Finland a significant part of social interactions take place between naked people, a somewhat disconcerting fact for most Europeans, and probably difficult to imagine in prude America. Where and how sauna emerged in the Finnish society seems to be unclear, but it certainly is so that religious pressure was less successful in quenching the need for hot baths there than elsewhere on the continent.

Sauna on the rocks

The weather was rather miserable, cold, wet and unpleasantly windy during the 2015 Summer, so that we stayed a couple days in Kasnaes before moving on to Nauvo where, the weather continuing to be miserable, we stayed again for some days, making a bus excursion to Turku. In Nauvo, a large place by Finnish archipelago standards, we met a long time friend and colleague astrophysicist, professor at the Turku University. He had a group of Russian scientists visiting and invited all of us at his cottage, some distance from the harbour.

There are very many such cottages hidden behind the first lines of trees along the coast. So many that in some, even very small, harbours, one sees a moderately large supermarket and rows of mailboxes. People use this infrastructure as base camps to keep the small boats they use to reach their cottage, and to purchase the food and goods they need to live on their isolated islands. The cottages are rather more like cabins than full fledged homes. They are used during the Summer months for holidays, the State being not so inclined to have these houses inhabited the whole year long, as this would imply keeping a much larger infrastructure, including for example schools, running all over the year. The cottages are hidden, as the law requires that they should not be visible from the sea. Our friend had built his himself, as many men do there. Tradition requires indeed, that every Finn man should have built at least one house in his life. Inevitably part of the afternoon we spent at our friend’s cottage was used for a sauna that included a swim in the 16° sea.

Each mailbox corresponds to a cabin somewhere along the shore or on an isolated island

From Nauvo we moved further west to Mariehamn in Aaland. Aaland is part of Finland, but not within the European Union. How this is arranged is unclear to me, but the arrangement suits everybody, as taxes, in particular on alcohol, are very low there. In addition ferries traveling from Stockholm to Turku or Helsinki making a short stop there are allowed to sell tax free goods on board. Mariehamn, like actually Turku, is a very, very quiet city. We did nonetheless enjoy a XIX century lieder concert in the local church.

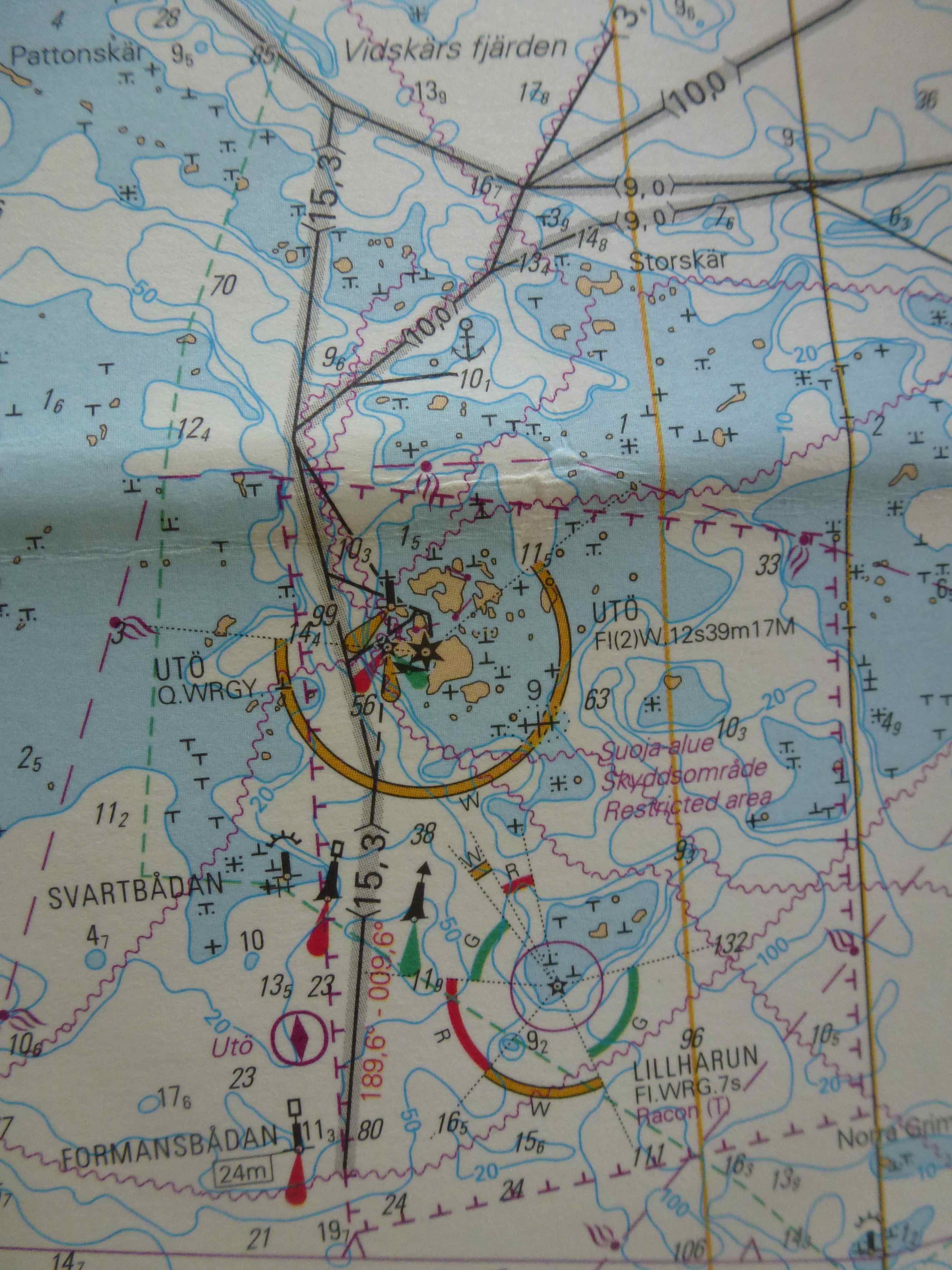

From there we moved southeast to reach Utoe, a rocky and windy island at the extreme tip of Finland. This was until few years ago part of an extended military region closed to civilian navigation. It now hosts a hotel open all year long. The recent military past is clearly recognisable by the large number of trenches and holes in the rocks and remains of canons. The population is about 35 in the Winter and 300 in Summer. That these numbers are sufficient to sustain a human social life was illustrated by a local marriage taking place the day we were there.

Arriving in Utoe

Utoe in the wind and sun

The next days saw us sailing east back towards Helsinki, where we left Cérès for the Winter. We enjoyed some magnificent sailing days following routes winding between NE and SE with mainly westerly winds. Barbara at the helm and I at the charts. We did not have much time for anything but keeping our route. We set the sails not so much to maximise the boat speed, but rather to keep a pace with which we could follow all the marks without missing any. It seemed to me that 6 to 7 knots was plenty.

We stopped in Rosala, another very small “harbour”. Actually these small places often have a wooden jetty around which one finds some buoys. One ties the stern to the buoy and the bow to the jetty. Rosala used to be a Viking centre. One therefore visits some reconstituted facilities from the Middle Ages. Among the displayed objects, there are models of the island in the course of the centuries. One sees on these models that the island grew significantly since the Viking time. This is due to a rise of the land. Scandinavia was covered during the last glacial period by a kilometres thick ice layer, which melted some 10’000 years ago. The weight of the ice on the land having disappeared, the land now rises at a speed of about 5mm per year. We thus noted that since our previous incursion in these waters, when our children were still very young, the land had risen by 13cm, or expressed differently, that there would be 13cm less water under our keel now than then. Meaning for example that some of the rocks just at the surface now would not have been visible then. This is geological phenomenology taking place at a pace sufficient to be noticed within the span of a life.

Our navigation had taken us in regions of rather large islands, predominantly close to the continental shore to parts of the archipelago dominated by small islands, most of them uninhabited. Rocks are found everywhere. The larger islands, also rocky, are covered by forest. Blueberries and wild strawberries grow generously under the trees. The rocks, be they bare or appearing in the forests have been polished by the glaciers to round, soft, almost voluptuous shapes. Asperities have been wiped out, making them most comfortable to walk onto. While their shapes are soft, their firmness is not to be questioned and contacts between hull or keel on one side and rocks on the other are to be avoided particularly when speeding along routes.

One of many small and delightful harbours of the Finish archipelago

Approaching Helsinki and looking back on the month spent in the archipelago, we noted that we had had very few contacts with people. We counted that we had exchanged more than 10 sentences with about 15 people over that period, including my colleague and his 4 Russian guests. Part of this is due to having spent few nights at anchor, part is due to the fact that not all Finns speak English comfortably, or to the bad weather that confined all of us inside heated boats, but this is mainly due to the fact that most Finns tend to speak very little. They don’t speak when they have nothing to say and evidently despise small talk, contrary to so many of our contemporaries. This makes contacts difficult, but gives a very special rhythm to conversations, in which silence is part of the exchange, and is amicable rather than hostile. We were nonetheless happy to spend our last evening in Helsinki with another astronomer colleague and friend, very popular in science communication in Finland, and his wife, both talking a lot, he having given a long interview in a national newspaper a few weeks before, naked in his sauna… .